Research and Geolocation

Returning the album later that week, I interviewed Dorothy for the article, who relayed that the album wound up in the attic of Seattle’s Teresa Duran Verfaillie before being donated to the archive and guessed that Caballero “must have been a friend of a relative” of Verfaillie, who held onto the album during a period of transition or after his passing. Searching digital newspapers, the University of Washington archive and books on the Internet Archive, I was able to place Salvador Caballero in time, finding him in the University of Washington Filipino Club in 1921, becoming a member and eventual Vice President of the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing and Allied Workers of America Union in 1939. Caballero appears in newspaper records one last time surviving a shipwreck off the coast of British Columbia, where he was working as a waiter aboard a Navy vessel destined for Ketchikan, Alaska, in 1941.

✺

Geolocation

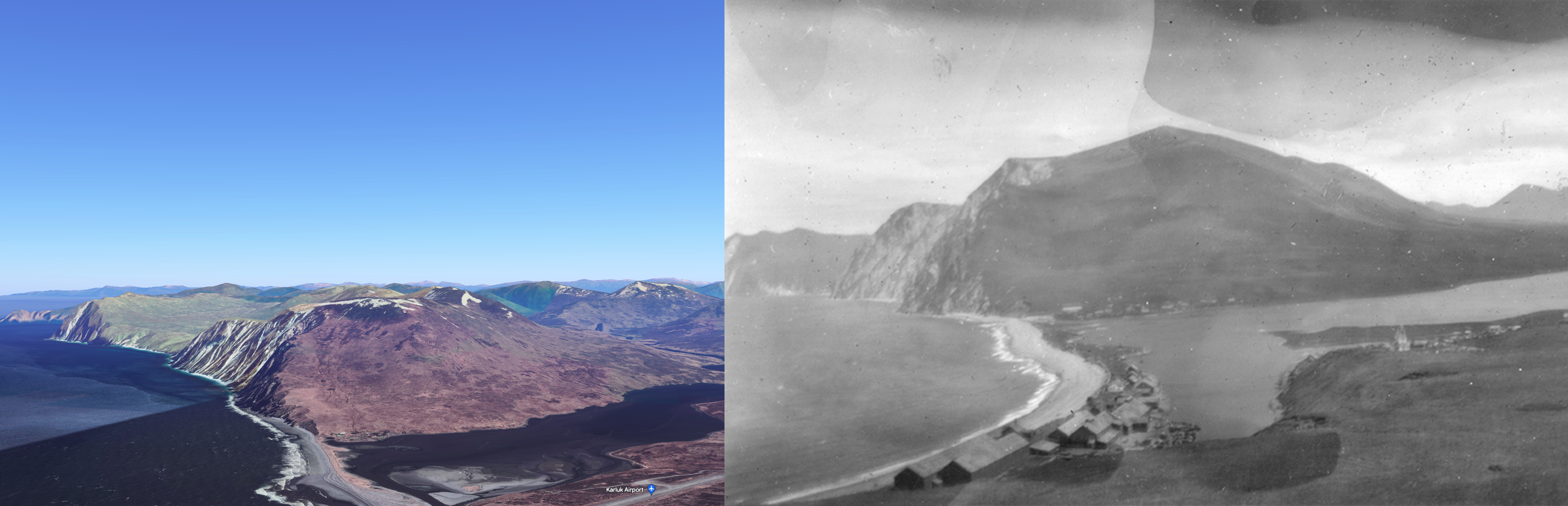

Because the Larsen Bay Cannery documented in Caballero’s photographs is no longer standing and the majority of the photos were unlabeled, Kodiak Island’s physical space was difficult for me to comprehend as a researcher. To these ends, I utilized Google Earth for geolocation. Surveying between the two geographic data points I had in Alaska, Larsen Bay and Karluck, a census designated area on the west side of the island, I was able to identify distinctive land features. This not only helped me fill in these metadata gaps but also provided context for the overall writing, helping me understand the dynamics of the cannery workflow, the space between cannery housing and Aluutiq residents and how far Salvador would venture out from Larsen Bay for recreation. Reverse image searching through Google Lens or Tineye can also be helpful for geolocation but tends to be more successful in identifying extant structures, with algorithms searching more for proportional shapes and identifiable text than geographic features.

✺