Process

Contents: Overview | Premiere | Python Text Mining | Primary Tag Sheet | Formatting | Apps Script | Copyediting

Overview

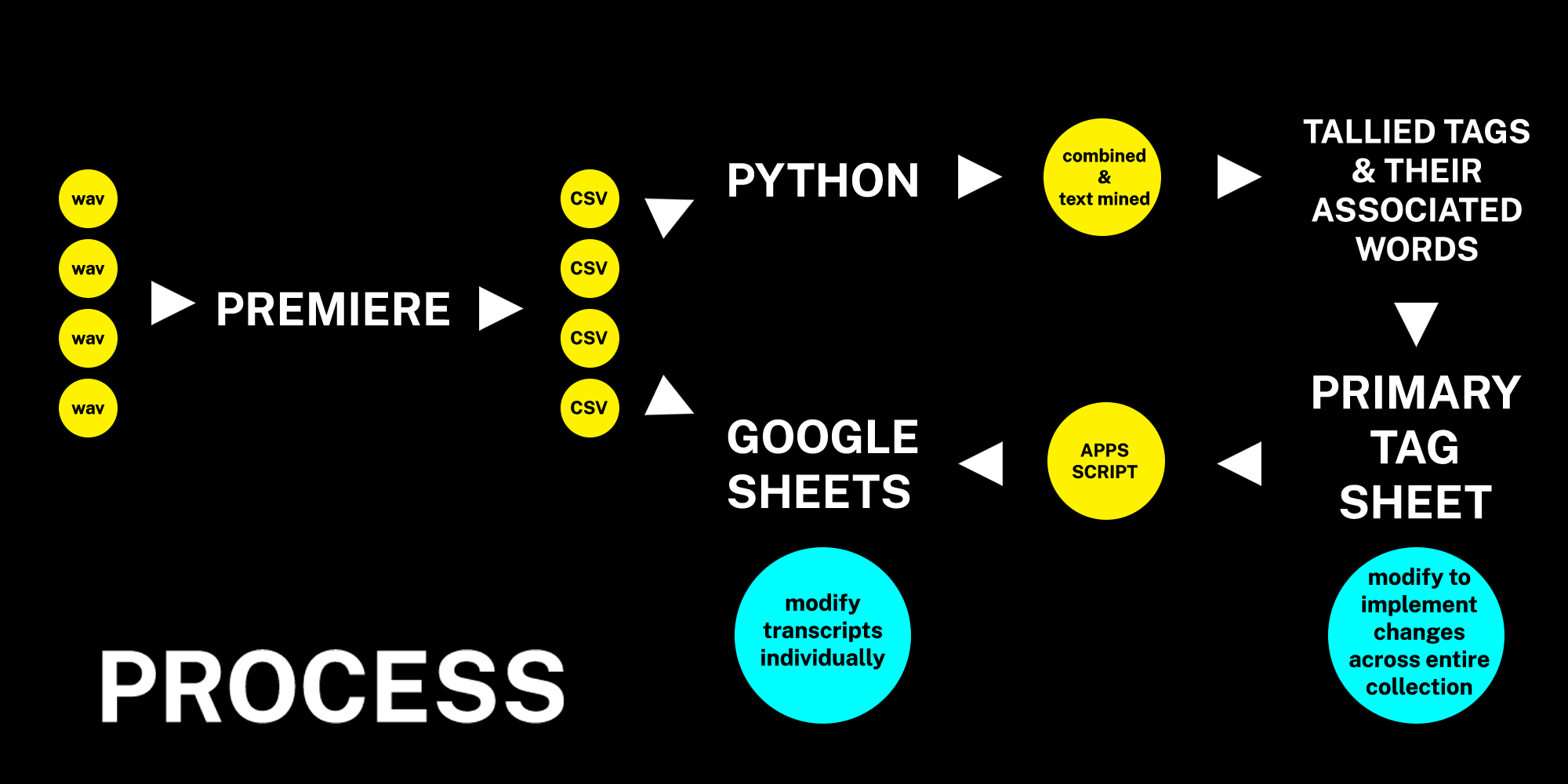

To summarize the process before going into detail:

-

Audio files are transcribed into CSV files be Premiere

-

These CSVs are made into individual Google Sheets and also added to the Python Transcription Mining Tool

-

Within the tool, these items are concatenated and this combined document is then searched for all of the associated words and phrases of each of the subjects built into the tool

-

The tool provides a tally of the identified associated words and subjects identified across all transcriptions

-

This data is used to create the “Primary Tag Sheet” in another Google Sheet

-

Using the Apps Script function, all individual transcripts are linked to the primary tag sheet so their tag fields are automatically filled with the subject head on the line of dialogue with the identified associated words and phrases

-

This way, new categories or associated words can be added or removed to the Primary Tag Sheet and these changes can be implemented across all individual transcripts by simply running the Apps Script

-

Individual changes can be implemented during the student worker led copy editing process to catch any data driven errors

✺

Premiere

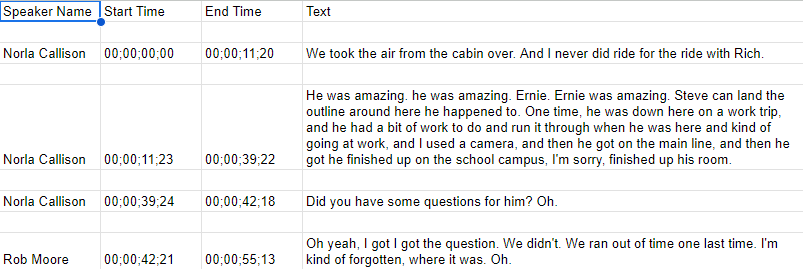

Drawing from my previous experience working oral history recordings for a digital encyclopedia, I tested Adobe Premiere’s transcription tools and found it uniquely well-suited for the Oral History as Data framework.

Advantages include:

-

Dramatically increased accuracy in differentiating speakers and transcribing dialogue, even with obscure and regional proper nouns.

-

Significantly faster transcription speed, from one 1.5-hour recording every two to three business days up to twenty 1.5-hour recordings in one day.

-

Costs covered by our university-wide Adobe subscription.

-

Direct export to CSV UTF-8 needed for OHD, avoiding conversion errors.

-

Free non-English language packs, enabling the creation of Spanish and French language oral history collections.

-

High privacy standards with Premiere’s GDPR compliance, ensuring all transcription material is stored locally and not uploaded to the cloud.[2]

That said, the tool is not a panacea. While modern recordings in good conditions have extremely high transcription accuracy, poor quality recordings or interviews between two similar sounding people can require significant copyediting. Recent work by the Matt Miller of the Library of Congress has me very interested in creating custom speech to text tools using Whisper(.cpp) to possibly help improve on these inaccuracies.[3]

To veer this tech talk into theory for a moment, while some negative perspectives of speech to text tools have to do with bias built into machine learning (Link, 2020), others stem from academic double standards expecting written transcripts to be an improved version of the audio rather than a reflection of it.

Some of these notions may originate from the American roots of oral history transcription at the Oral History Research Office of Columbia University in 1948, where editors were encouraged to delete “false starts”, audit wording, rearrange passages into topical or chronological order or delete whole sections to transform the transcript from “what might be dismissed as hearsay into a document that has much the standing of legal disposition”, essentially divorcing the transcript from the audio.(Freund, 2024) Since then, critics of this practice of “cleaning up” spoken language have emerged, pointing out how it introduces unnecessary editorial bias. As University of Kentucky’s Susan Emily Allen notes in Resisting the Editorial Ego: Editing Oral History:

These texts take it upon themselves to glean "what words are meaningful." Meaningful for whom? For the editor? Such subjectivism is not only rather irresponsible scholarship but, however well-intentioned, an attempt to legislate truth. (Allen, 1982)

✺

Python Text Mining

After initial tests using the web based text mining tool Voyant while developing the Taylor Wilderness Research Station digital collection, I wanted to create a text mining tool from scratch using Python that would allow me to identify specific words and phrases, create custom tagging categories and “stopwords”(words removed from text before processing and analysis) for each collection.

Once the CSVs of the transcript are added to a folder in the Python workspace, the code begins with importing Pandas library for data manipulation, the Natural Language Toolkit and TextBlob for language processing and sentiment analysis. Additionally, Regular Expressions and the ‘collections.Counter’ function are added for text mining and tallying results.

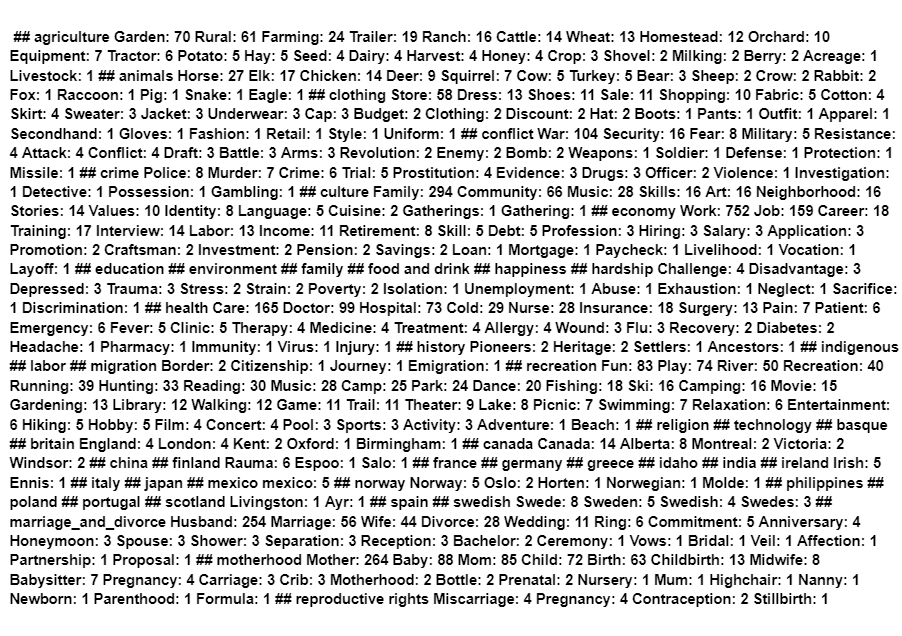

Next, the ‘preprocess_text’ function removes words of four characters or fewer, eliminates punctuation, and converts all text to lowercase. CSV file paths are constructed, and the text data is concatenated into a single string corpus. Stopwords are removed, word frequency is counted and the 100 most frequent words are generated when the code is run.

Below this header material in the Python file are three categories: general, geographic and custom. These categories contains sections, which will ultimately become the tags:

-

General: agriculture, animals, clothing, conflict, crime, culture, economy, education, environment, family, food and drink, happiness, hardship, health, history, indigenous, labor, migration, recreation, religion, technology

-

Geographic (based loosely on migration statistics from the 1910 Idaho census[4]): basque, britain, canada, china, finland, france, germany, greece, idaho, india, ireland, italy, japan, mexico, norway, philippines, poland, portugal, scotland, spain, sweden

-

Custom (example from our Rural Women’s History Project): Marriage and Divorce, Motherhood, Reproductive Rights

Each section has a list of fifty associated words that the script is searching for within the concatenated text corpus. These were generated using Chatgpt with the following qualifications:

-

Specifically related to the section topic (e.g., agriculture, animals)

-

Exclude homographs (words that are spelled the same but have different meanings)

-

Place names and how certain nationalities would refer to themselves for the geographic sections (e.g., “Finnish”, “Suomalainen”, “Finland”, “Suomi”, “Helsinki”, “Espoo”, “Tampere”, “Vantaa”, “Oulu”)

✺

These produced a total of 2,250 associated words across the 45 sections. The script then tallies these words and produces the output shown below:

Future iterations of this template will modularize the General, Geographic and Custom sections for easier navigation instead of its current form as a single, expansive Python file. See Appendix 1 in the final section of this site for an excerpt of the current iteration of this code or the entire GitHub repository that is linked on the landing page to the site for this presentation.

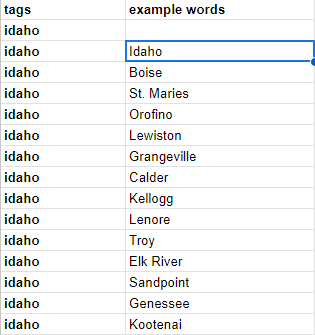

Primary Tag Sheet

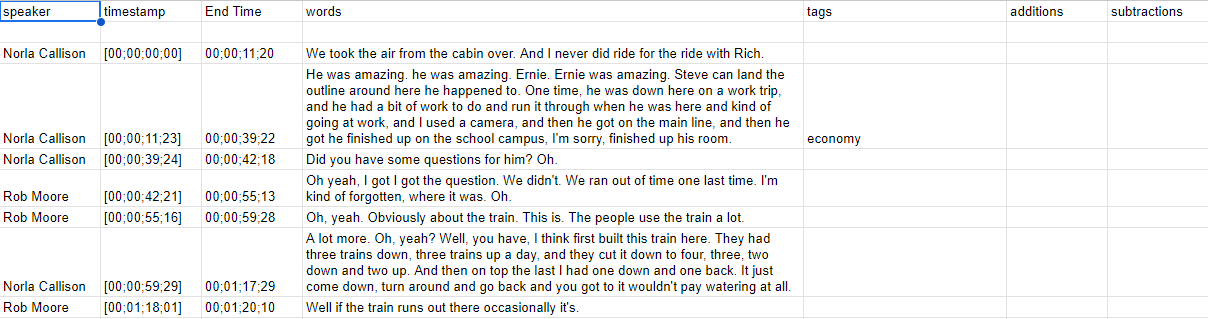

Once this text mining data is produced from the combined transcripts, it is entered into a “primary tag sheet” in Google Sheets, located in the same folder as the transcripts for student workers to edit. Using the Text to Columns function, tag names are split into column A and their associated words into column B.

Formatting

The student workers then open their transcription sheet to make the following changes necessary for the Oral History as Data framework, including:

- Removing rows between dialogue

- Revising header semantics (e.g., Speaker Names to speakers, Start Time to timestamp)

- Adding brackets to timestamps

Apps Script

The student worker then opens the Apps Script extension on the transcription sheet and enters the code detailed in Appendix 2. Transcribers only need to make two adjustments: change the sheet name of the transcript they are editing on line 6, and the URL of their primary tag sheet on line 13, then save and run the code. This will automatically search the text for these associated words and fill in their tag name within the tag column of the transcript.

✺

Copyediting

This process is not intended to replace human transcribers, rather shifting the focus from manual tagging to copy editing, reducing heavy lifting and repetition. If a tag is inappropriate, the transcriber pastes it to the additions or subtractions column so these changes are preserved for future runs of the Apps Script and reflected in the final import to the OHD digital collection.

Crucially, student workers are encouraged to modify tag names, add or remove associated words and create new categories based on trends they identify within the primary tag sheet. Once these changes are made, the Apps Script can be quickly re-run on all transcripts to implement these updates . Rather than simply asking student workers to transcribe recordings—work that offers little to highlight on a CV and can lead to burnout and high turnover—this process allows transcribers to engage in coding, create and modify tags, and see those changes reflected instantly through the Apps Script process.

Other advantages include:

- All tags use a controlled vocabulary.

- Tagging is more accurate, detailed, and relevant, helping researchers quickly identify thematic connections.

- Tagging establishes a knowledge framework relevant to the collection that transcribers might lack in historical, scientific, or regional contexts key to the recordings.