Sound and Embodiment

The Empathetic Power of Sound

The addition of the voice, whether it is yours, interviewees or oral history recordings that you are utilizing, gives listeners more empathetic context for why they should engage with your story. Visiting the space you are writing about and using portable recording equipment, referred to as field recording, can provide listeners with a sense of place.

Ambient audio of a landscape is uniquely context dense, conveying remoteness, urbanity, vegetation density or sparseness, human or animal activity and even the shape of the geography–all without words. Additionally, this is audio information that most listeners can take in while also paying attention to a narrator, because that is the kind of multi-channel multi-tasking that we always do when we navigate through the world.

Embodiment

Those were all reasons that using an audio medium can be more engaging for others, but the most important thing for you as a researcher in environmental history, archaeology, geology, journalism or interdisciplinary sciences is how it enriches your own understanding of your research subject. While visiting the location you are studying is a fairly straightforward strategy for gaining more context, focusing on recording interesting audio, exploring a space from many angles and interviewing people that live in the area is a form of embodiment. This concept that human experience, perception and interaction with the natural world is rooted in physical, lived experience and that sensory information informs how people understand a landscape.

Embodiment is often used to complicate what we think we know about an area and challenge the objective rationalism of science by exploring how researchers reflect their own life experience onto their subjects. In the words of author Christopher Sellers, the embodied approach to understanding place is mindful not only of a researcher’s “geographical ties to a particular place” or their “dependence upon individual perspective and experience; rather, their bodily situatedness to facilitate knowledge-making.”1 Essentially, this means that researchers should be mindful of their bias that they bring to their subjects and focus on the immediate, physical experience of exploring that space to create new discoveries and connections.

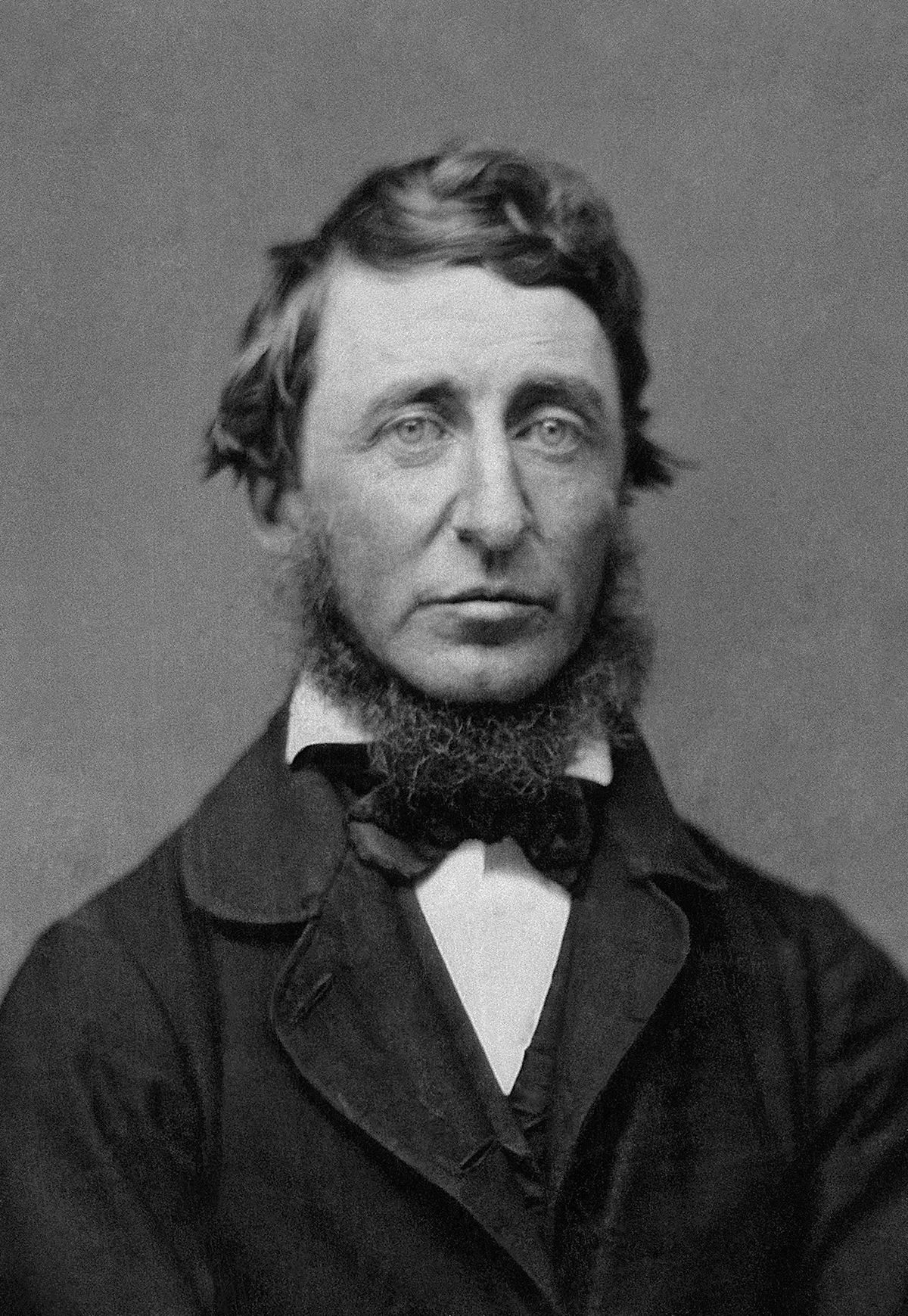

Examples of scholars using embodiment techniques to understand places in new ways go as far back as naturalist Henry David Thoreau living and working in Walden Pond and geologist James Hutton making discoveries about deep time and uniformitarianism through repeatedly walking and observing rock formations in Scotland. In the 1990s, archaeologist Christopher Tilley explored how prehistoric people interacted with their landscape by walking and studying burial mounds and stone circles in the UK, assessing physical movement and visibility to reassess how these people navigated the landscape. More recent work by researchers approaching embodiment from sound design have explored how field recording can capture the subjective experience of the recordist’ physical engagement with the environment.2

✺