Findings

Despite the Edge Detection tool working with seemingly more complex materials in archeological items with intricate edges, while the Image Extraction tool is generally working with rectangles, the latter is much less accurate. I think this is due to coincidental similarities of archeological photographs and the commercial photography that IS-NET was developed for. Both use fairly new cameras at close range and identify and extract a single, principle object in each image. The model is extensively trained because, unsurprisingly, there is incredible economic interest in streamlining the digital processing of commercial products and it just happens to overlap with this academic and preservation oriented discipline.

✺

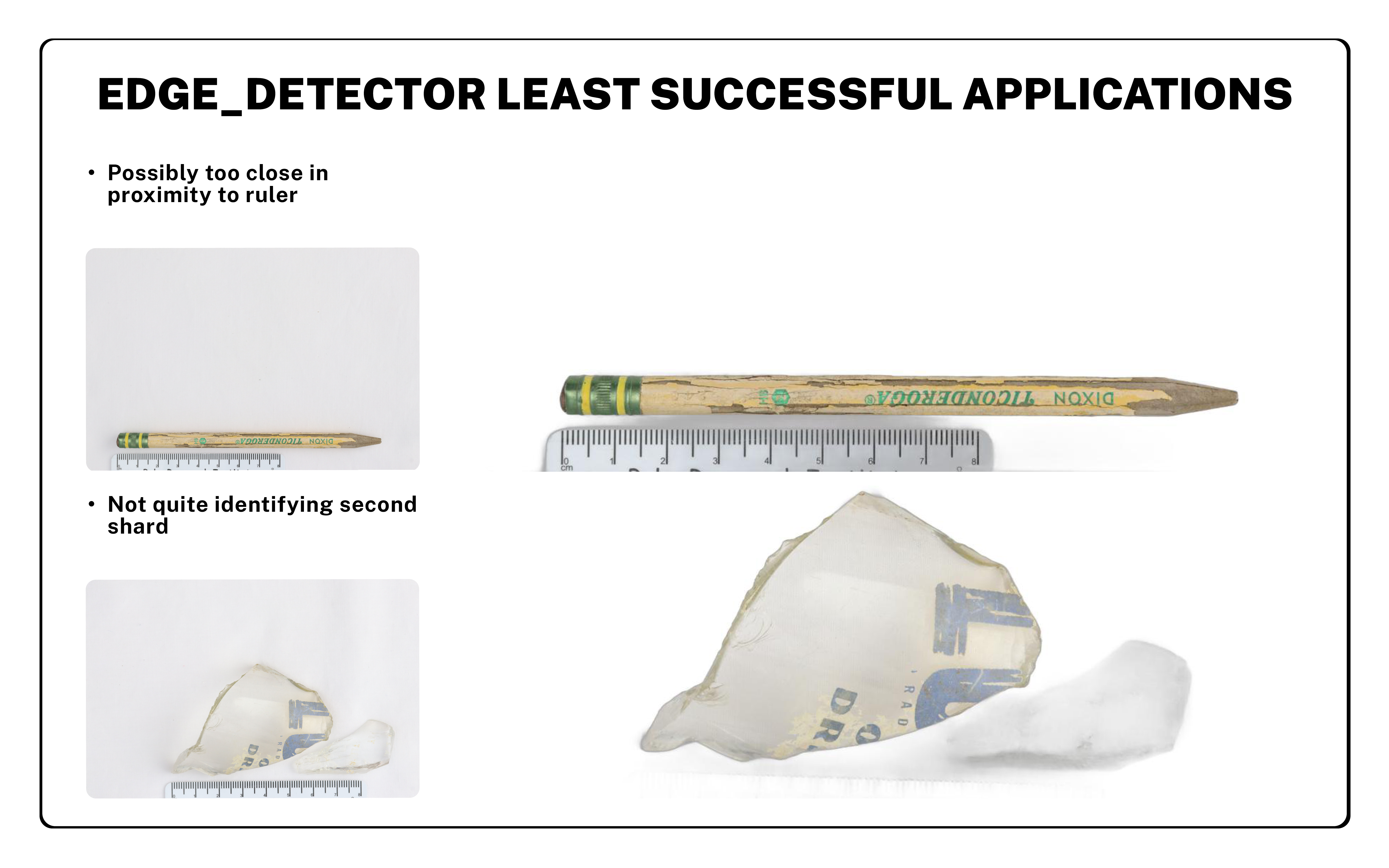

On the 24 objects I tested with this tool, including some tricky, nearly transparent glass items, the tool only produced three minor inaccuracies: Even though the code specifies only finding a single, principle object in each image, the tool successfully extracts both shards of nearly transparent glass in the bottom image, but it also includes a very slight shadow, and the ruler next to this pencil is being lumped into the extracted image, possibly due to proximity. Additionally, there is one object you can see on the banner for this presentation that I will return to, where some of the text within the paper wrapper has been misidentified as it’s black background.

✺

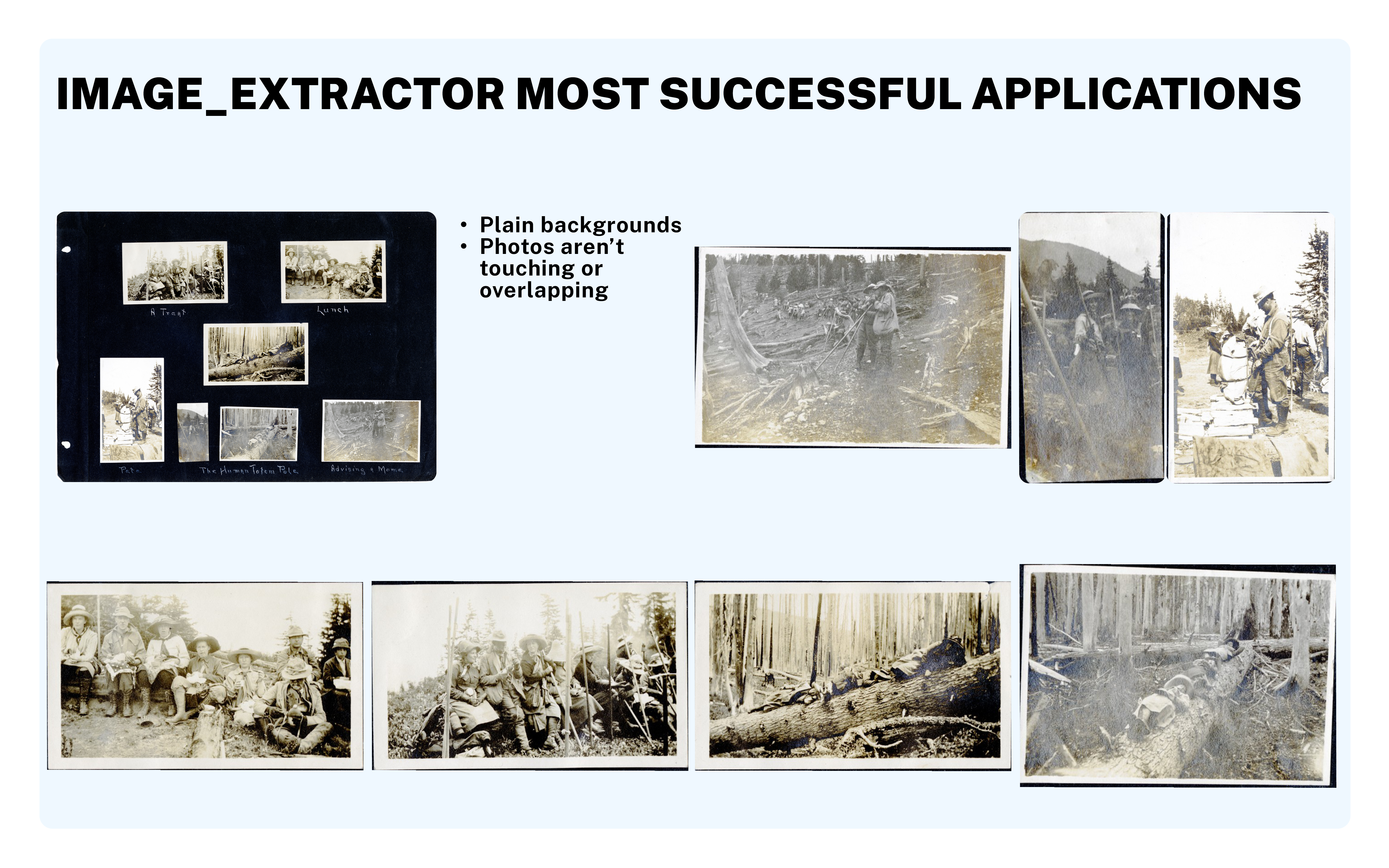

In this example of a scrapbook page with a plain background and fairly straight, somewhat evenly spaced photos, it identified and correctly extracted 25 of the 26 images, although there are still minor inaccuracies around the margins of the photographs, not fully rotating the images to 90 degree angles.

✺

In these two examples where photographs within the scrapbook page are skewed, overlapping, touching the borders of the full image, on paper containing designs or containing multiple background colors, the success rate of extraction was around 73 percent. At that level of accuracy, you might be better off approaching these projects manually.

Despite seeming more geometrically straight forward, extracting photographs within scrapbooks involves a deceptive amount of variance. The shapes of photographs may be rectangular, circular or with scalloped edges. The background paper may be white, beige or black. Additionally, if a photograph is extracted successfully at a right angle, the image itself may be skewed within the border. All of this, along with the complication of identifying multiple objects, which allows for the possibility of false positives in the form of noise within the page, made this a more complicated task than I would have assumed at the outset.

It’s no wonder the edge detector, at a slim 45 lines of code and built around a single, extensively trained model, performs more accurately. The image extractor is twice as long and relies on multiple machine learning libraries to resolve the many potential conflicts which may or may not be involved in it’s task.

✺

Conclusion

My biggest take away from working on these tools is to seek out models working in parallel disciplines which may be much more well funded than the archives. I “developed” these tools so far as I implemented an infrastructure for different machine learning and neural network models to produce outputs in the format that best serves our preservation needs at U of I, but the development of those models took so much more time and technical expertise than I will ever have as a librarian. That said, if we can identify these these parallel applications in better funded commercial spaces that have analogues to our materials, we can leverage them to create open source, scalable tools for digital processing to increase the efficiency of our archival practices.

About the Author

Andrew Weymouth is the Digital Initiatives Librarian at University of Idaho, primarily focusing on static web design to curate the institution’s special collections and partner with faculty and graduate students on fellowship projects. He has also created digital scholarship projects for the universities of Oregon, Washington and the Tacoma Northwest Room archives, ranging from long form audio public history to architectural databases and network visualizations. He writes about labor, architecture, underrepresented communities and using digital scholarship methods to survey equity in archival collections.