Introduction

Hello, my name is Andrew Weymouth and I have worked with the University of Idaho Library as the Digital Initiatives Librarian in the Center for Digital Inquiry and Learning (CDIL) department since the fall of 2023. My work generally consists of creating and maintaining our digital collections, collaborating on projects with fellowship recipients, helping to rethink processes and introducing new digital scholarship tools to the department.

✺

Why Geolocate?

To start, I’d like to share an example of how geolocation, or the process of identifying where a visual resource was captured, can enhance your research. In the summer of 2023, I was writing about Filipino American “Alaskeros” who migrated seasonally between California, Oregon, Washington, and Alaska to work in salmon canneries.

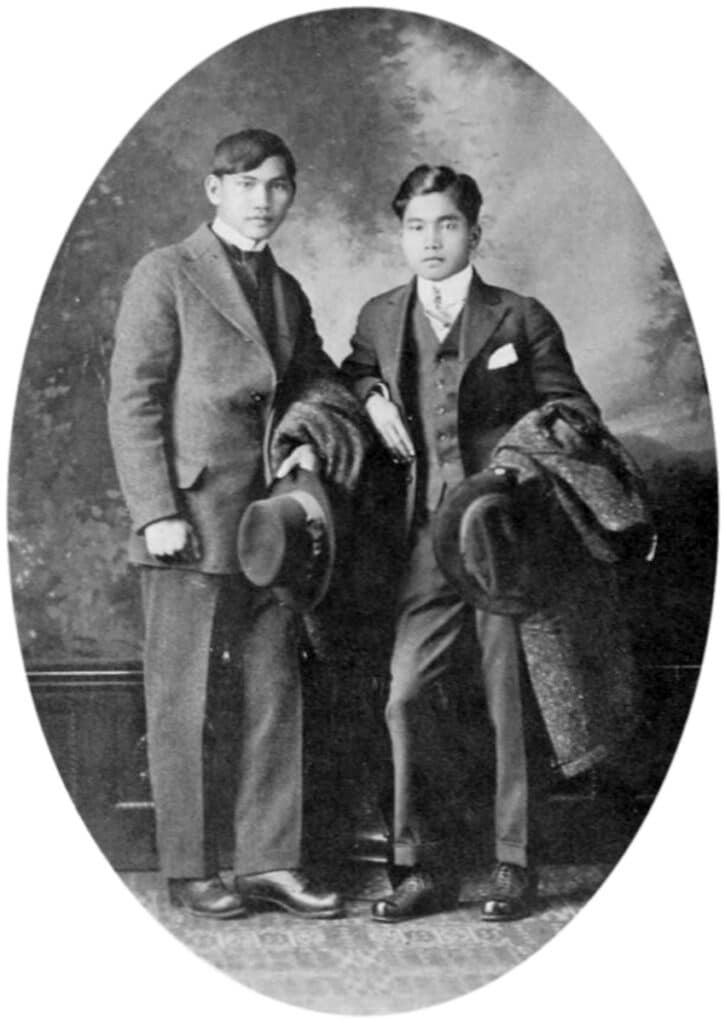

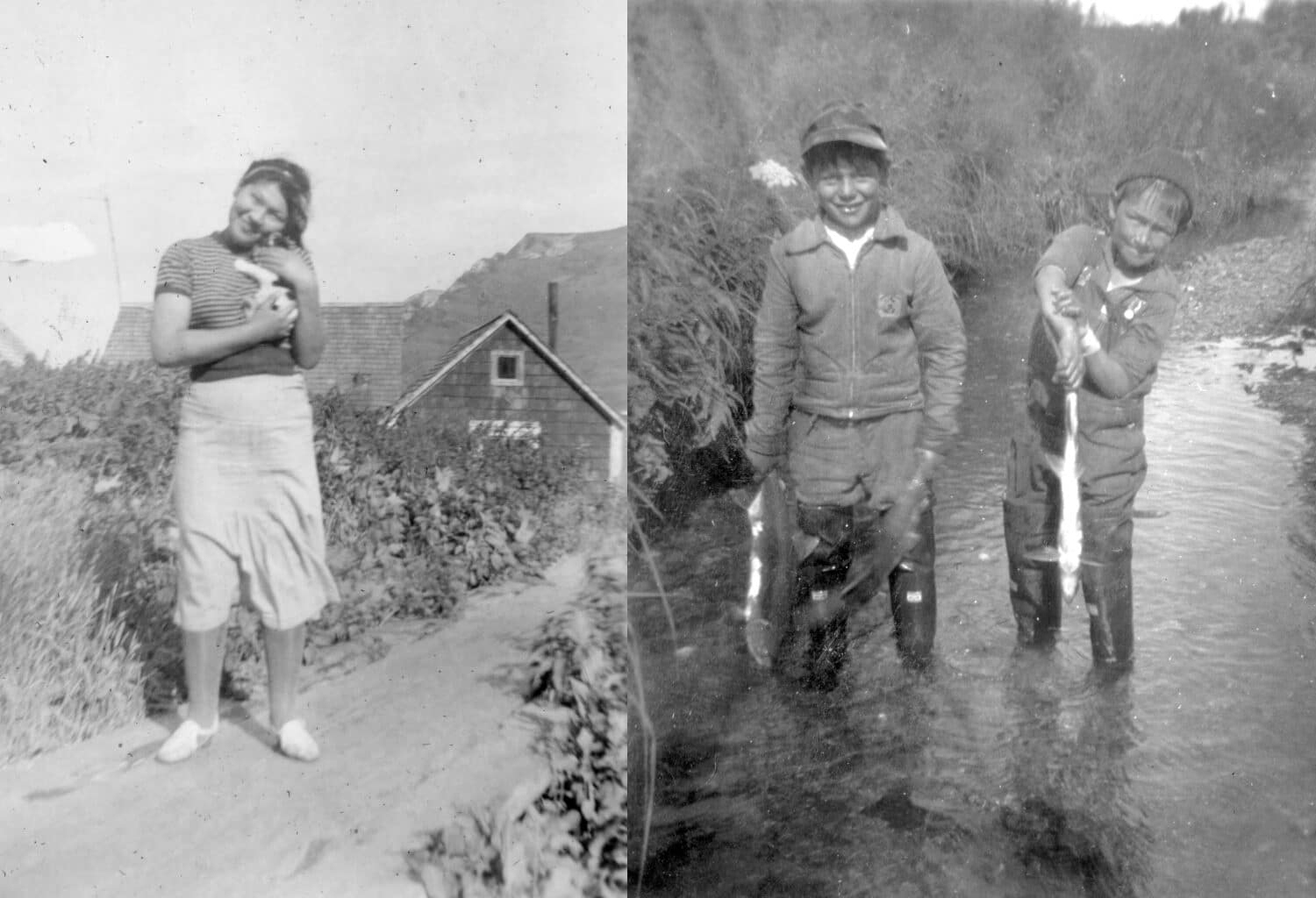

One of the only first person resources I was able to find from this community of migratory workers was a scrapbook of an Alaskero named Salvador Caballero, housed at the Filipino American National Historical Society in Seattle. Caballero’s photos offer a candid view of migratory life, but only a few of the hundreds of images include location notes, making it challenging to fully grasp the insights they could provide about travel, labor, unions, and daily life.

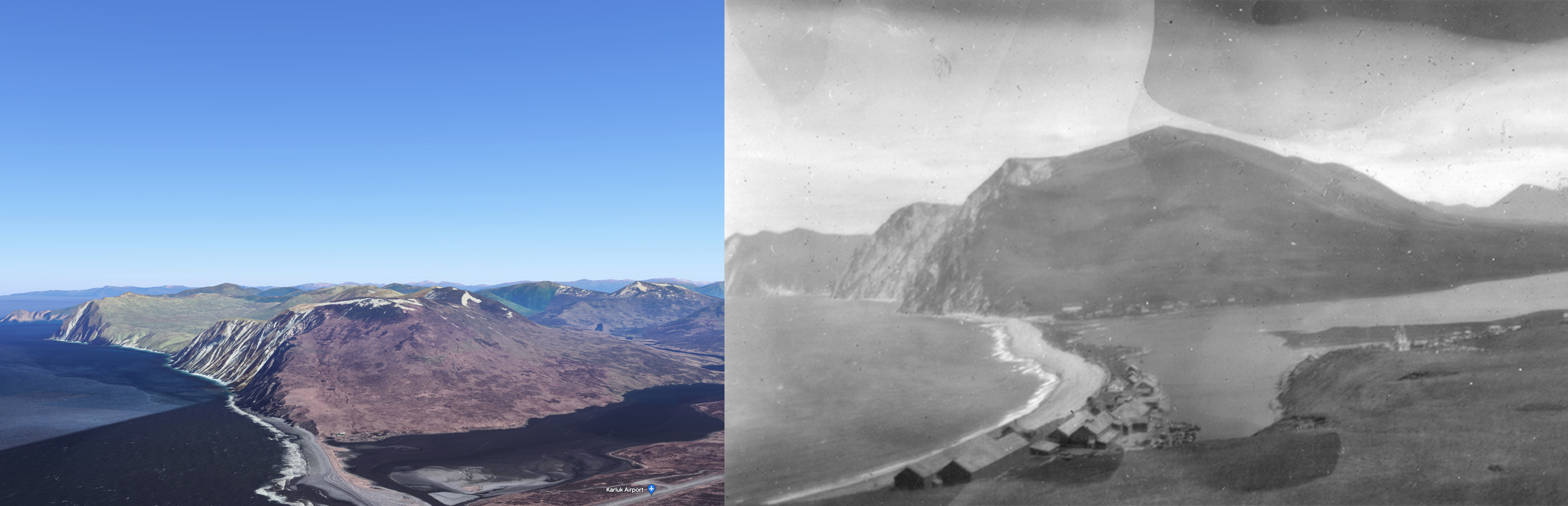

Though the platform has been in development for almost 20 years, continued improvements in satellite imagery and recent advancements in 3D technology have made even remote areas of Alaska identifiable through Google Earth. A note in Caballero’s scrapbook mentioning the “Karluk Cannery” allowed me to use a basic geolocation technique: tracing the coastline of the southeastern Alaskan island of Karluk in Google Earth to match natural landforms in the photo collection. When working with an island or similarly contained area, this process is relatively simple, as coastal rock formations tend to remain consistent over time.

✺

By connecting landform, monuments, bodies of water and building footprints between photographs and satellite imagery, an entirely new layer of historical context can be drawn from an archival image. Travel distances can reveal how much free time workers had, the layout of housing and its proximity to indigenous communities can shed light on race and class dynamics. Additionally, analyzing the distance between the cannery site and the fishing grounds located further south helps us understand day-to-day business practices and the logistical challenges faced by workers.

This presentation introduces tools and methods for geolocation to help you enrich your own research and make new academic discoveries using visual resources. The following sections have been organized as a kind of workflow: moving from the most intuitive, straight-forward to more complicated, technical approaches.

Note

All of the tools I will be covering today are freely available resources you can access as a U of I student, though some will require you to submit an form beforehand stating that you will be using them for non-profit purposes.