Reverse Image Searching

Similar to Google Earth’s satellite imaging, reverse image searching has been under development for many years, but recent innovations have significantly improved its accuracy. This technology works by using an algorithm to analyze an image’s content and create a unique digital signature, or “fingerprint.” The algorithm then searches for similar fingerprints within the platform’s database. The first publicly available reverse image search engine, TinEye, was launched in 2008, followed by Russia-based Yandex, and then Google and Bing.

✺

- For an exact image match, such as when verifying the copyright of an image without metadata, I recommend using TinEye

- When you need to identify an area that may be taken from a slightly different angle, lighting or proximity, I recommend using Google Lens or Bing Visual Search

- These algorithms excel because they are able to detect particular digital signatures that align with your image from an otherwise contrasting image, such as one distinctive structure or the particular shape of a skyline

- While Yandex is by some accounts the most accurate of all of these tools for geolocation, I’ve found that search results skew heavily towards locations in Russia and Europe

Here are some examples of the types of things reverse image searching excels at and some of the things it struggles with:

✺

Strengths

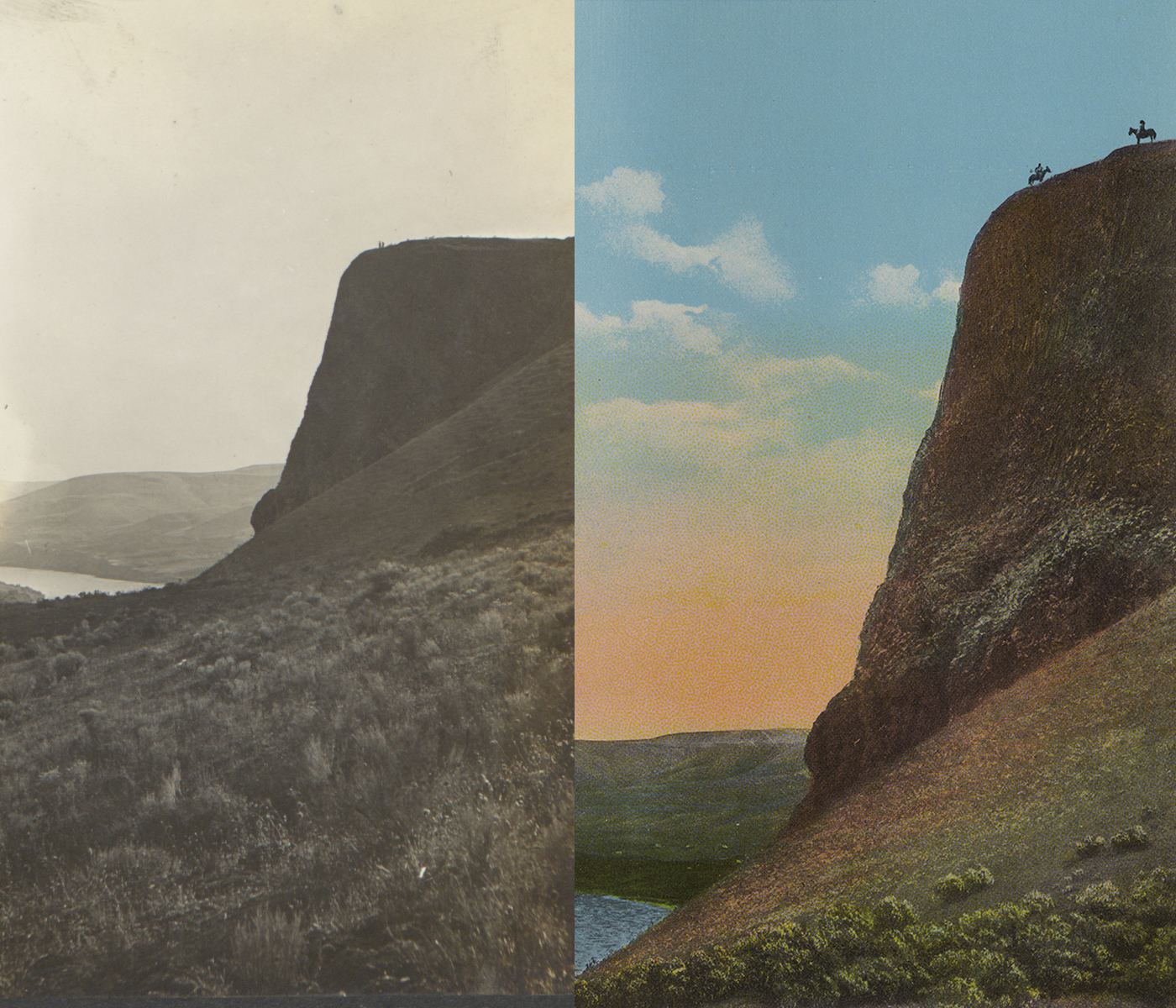

- Dramatically distinct patterns in the landscape, as in this Swallows Nest Rock on Snake River located in Clarkston, Washington.

Many of these roadside attraction type images are readily identifiable simply because the lookout areas often mean that people have been taking the same photos of the same things from the same perspective for 100 plus years, so there are plenty of digital fingerprints in any given database to reference!

- Distinct patterns in the built environment are also effective.

The same image we located through text analysis is also identifiable through reverse image searching. Although we don’t have an explanation of what the Google Lens algorithm matched between this photo (PG070-66-01) and this one, taken from a significantly different angle, it would be surprising if it wasn’t the distinctively shaped little white building on the bottom left of both images with its heavily contrasted doors and windows creating a unique digital fingerprint.

The pattern of the bridge and geological markings helped identify the now demolished Spalding Bridge on the Clearwater River east of Lewiston (PG070-18-01) and the festivities indicate this may have taken place during the opening ceremony of the structure in 1923.

✺

Weaknesses

- Popular text against nondescript surroundings

There were hundreds of unrelated National Geographic results that were generated for this image, but none having to do with this strange piece of roadside architecture.

- Residential architecture

These types of houses were literally sold in catalogs, making these digital fingerprints too universal to identify with reverse image searching.

- Sparsely populated areas

The lack of distinctive digital signatures, and the higher likelihood that the area has possibly never been photographed before and the success rate of reverse image searching much lower.

- Pervasive industrial structures

Like residential architecture, reverse image search tools struggle with common industrial structures, which often lack distinctive digital fingerprints and are often so large that they can obscure valuable context in the skyline.