Obsidian

Now that we have our two markdown files of the extracted annotations and their highlight categories:

- Open your Obsidian vault

- Create a folder for the book or document you just processed

- Drop the two markdown files inside.

While there are more complicated ways to search for things in Obsidian, the only elements that we really need to use this method are searching a path and for tags. Paths are simply refining results by how you have organized your folders, whereas tags are custom categories you create by adding a hashtag (#) before each entry in your markdown file.

◒

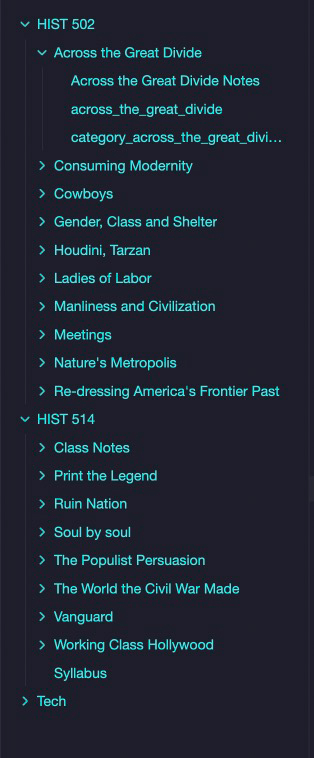

For example, if you have arranged your folder like the image below:

By entering “path:” into the search bar on the left side of the screen, you can choose to either see only HIST 502 or HIST 514 and all of their associated texts or individual texts in either the graph or document view.

Additionally, if you type “tag:” you will now be able to see the six tags that we’ve generated from the highlighted text by having the python tool insert a hashtag in front of each of these categories. But let’s build off of these initial categories in the review and custom tagging process.

✺

Review and Detailed Tagging Process

While you can do detailed tagging in either file, I’ve found that this process makes the most sense in the chronological export, but I still like to have the categorized markdown file in case I want to look at just the “important” or “stats” sections. Whichever file you choose to do detailed tagging on, think of this as your primary notes document moving forward.

At this point in your research, you’ve read this text once and highlighted sections based on category. While you are reviewing these notes again, take a moment to reassess the initial tags (perhaps an #important passage is actually a #general note or the reverse) and, most importantly, create new tags. Perhaps an #important passage you’ve initially highlighted in animal sciences also has to do with #livestock-genetics,#animal-nutrition or #behavior-ethology? Maybe your initial tag of a #quote in a book covering botany is also indicative of larger themes you would like to track about #plant-morphology, the #photosynthesis-process or #ecological-interactions that you would like to see together at a glance?

Note that tags need to be connected by dashes or underscores if you want to use multiple words and that you can also create sub-tags to analyze different elements under the same parent item by putting a forward slash after the tag, such as #author/thesis or #author/methodology or author/questionable if I find something a little suspect.

✺

Tagging is an iterative and subjective process. You may find that throughout the course of your research, the name of the tag may shift as you think about that subject differently. Four or five tags may merge into one as you begin to identify major themes that emerge across the collection. Before reviewing material, I find it helpful to expand the tag panel on the right side of the interface and quickly review tags to remind myself of an ever expanding list to keep redundancies to a minimum.

Though this second review of the material may feel like an extra step, I’ve found that it not only helps me make more sense of the material but the tagging process taps into an active, creative engagement with the text as I look for ways that it compliments or criticizes other work in the vault. One of Obsidian’s strength is that it isn’t just a keyword search across a pool of notes. Instead, you are adding meaning making tags that are particular to what you are finding in the text to form the interconnected “web of knowledge” across the collection. Which is a good jumping off point to the final section on the visualization of this research.